圖/莊坤儒

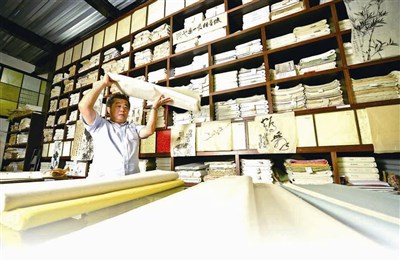

南投埔里廣興紙寮經營手工造紙近50年,第二代經營者黃煥彰研製的高級書畫紙,在書畫藝術圈內名氣響亮。

圖/莊坤儒

南投埔里廣興紙寮經營手工造紙近50年,第二代經營者黃煥彰研製的高級書畫紙,在書畫藝術圈內名氣響亮。 圖/莊坤儒

除了打造高級書畫紙,廣興紙寮也是台灣第一家手工紙觀光工廠,每年吸引超過20萬人次到訪。

圖/莊坤儒

除了打造高級書畫紙,廣興紙寮也是台灣第一家手工紙觀光工廠,每年吸引超過20萬人次到訪。 圖/莊坤儒

除了打造高級書畫紙,廣興紙寮也是台灣第一家手工紙觀光工廠,每年吸引超過20萬人次到訪。

圖/莊坤儒

除了打造高級書畫紙,廣興紙寮也是台灣第一家手工紙觀光工廠,每年吸引超過20萬人次到訪。 圖/莊坤儒

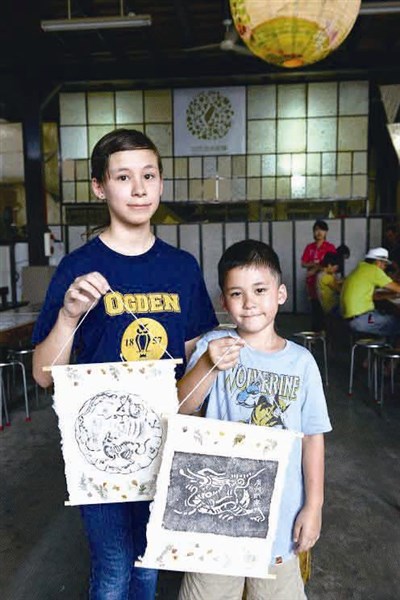

來到廣興紙寮,遊客可學習親手抄紙,也可在手工紙做成的藝品上,拓上自己喜愛的圖案。

圖/莊坤儒

來到廣興紙寮,遊客可學習親手抄紙,也可在手工紙做成的藝品上,拓上自己喜愛的圖案。

提 要

什麼紙,讓書法家侯吉諒讚嘆「最好的紙,就在台灣」?

也讓大陸、日本、韓國書畫家上癮,專程來台搜購?

從代工起家,到做出各式可寫、可畫、可吃、可穿的高級紙,

位在南投埔里的廣興紙寮,創造出手工紙業谷底翻身的傳奇。

Crossing the Ai lan Bridge, our car enters the Ai lan Plateau, the gateway to Nan tou County's Puli Township and the only locale in Taiwan now producing handmade paper. Of the passing tour buses full of elementary or junior high school students, eight or nine out of ten are on fieldtrips bound for the Guang xing Paper Mill.

Seventeen years ago, the Guangxing Paper Mill became Taiwan's first tourist factory making handmade paper. Today it attracts 200,000 visitors a year and has become Puli's newest calling card.

Paper, gunpowder, the compass and movable-type printing are regarded as ancient China's four greatest inventions. Although the Chinese invented paper, Puli has inherited the improved tools and methods that were traditional to the Japanese. Here you often see paper made with boiled tree-bark fiber. After the pulp is placed into a trough and blended, a bamboo screen is used to lift out a thin layer of fibrous pulp. After drying over heat, the resulting sheet of paper is well suited for calligraphy or painting.

In the 1990s, amid low-cost competition from mainland China and a sharp decline in the number of people learning calligraphy in Taiwan, factories began to move to Southeast Asia, and Puli’s handmade paper industry was declared to be in its sunset.

Currently only six paper mills remain in Puli. Among them, Guang xing has established a niche for itself as a maker of traditional, high-quality paper for painting and calligraphy. In recent years it has released papers of unusual design or texture for use in innovative “cultural and creative products,” edible paper of various flavors, and paper fabric that can be used as material for clothing. It has staked out a unique place in the paper industry, keeping the legacy and traditions of Taiwanese handmade paper alive while opening up new creative horizons.

In the early 1990s, Huang Yao dong wanted his son to take over the business. By then, the handmade paper industry was already in decline, but Huan zhang, over 30 and lacking any other work experience, summoned the courage to take over the family firm.

One day, he noticed a calligraphy on the wall, as well as the signature of its calligrapher: Tai Jing nong. “Why don’t we just sell directly to the end user?” he thought. It was a turning point: He had transformed his frustration into single-minded determination to find a solution.

Huang Huan zhang says that those three characters—Tai Jing nong—were like a blow to the head that prompted a sudden understanding: Guang xing shouldn’t be concerned with paper dealers; it should focus on the needs of painters and calligraphers. From that moment on, Huang started to collect the names of painters and calligraphers to send them paper samples for free.

By supplying those artists with paper, Guang xing received a steady stream of suggestions, which guided improvements.

Apart from producing traditional paper for calligraphy and painting, Guang xing has in recent years achieved some notable successes with paper taking new “cultural and creative” directions. These achievements have largely been thanks to the behind-the-scenes work of Wu Shuli, Huang Huan zhang’s wife.

Creativity is Wu Shuli’s strong suit, and since joining Guang xing she has constantly wondered: “In what new ways can handmade paper be adapted?”

At vegetable markets she saw surplus vegetables that hadn’t sold being thrown away. In order to prevent waste, she came up with the idea of using those vegetables to make paper.

The quick-witted Wu asked her husband to install a papermaking station in her kitchen. Apart from taking special steps to ensure cleanliness, the process was exactly the same as at the factory. She tried a variety of vegetables including chayote shoots, water spinach, sweet potato leaves, sponge gourd, pumpkin, and chili pepper. Eventually, for the 100th anniversary of the ROC, the company released 100 kinds of edible paper that could be used for snacks or seasoning. They called these “vegetable papers.”

“Making paper is a lot like composing music; it requires variation,” says Wu, who is happy to share what she has learned.

In July of 2013, she went on to release a waterproof paper fabric, which is suitable for use in theatrical costumes and rental clothing. But for this new line they went back to using wood pulp. “We returned to our ‘tree roots,’ as it were, in making handmade paper,” she says.

翻 譯

車子穿過舊稱烏牛欄橋的愛蘭橋,來到愛蘭台地。這裡是進入南投埔里的大門,也是台灣唯一生產手工紙的地區。過了愛蘭橋,路上穿梭的中小學戶外教學遊覽車,十之八九以廣興為目的地。

十七年前,廣興紙寮即成立全台第一家手工紙觀光工廠,打破工廠與教室之間的隔閡,讓參觀者邊看、邊學、邊做,近來每年吸引超過二十萬人次到訪。在茭白筍與埔里酒廠之外,廣興紙寮已經成為埔里新的招牌。

造紙、火藥、指南針及活字印刷並稱中國古代四大發明。二千多年前,東漢蔡倫以樹皮、短麻、破布、廢漁網造紙,相傳是紙的始祖;但也有考古證據指出,更早之前即有紙的存在。

雖然紙是中國人的發明,但埔里所承襲的造紙術,卻是日本人改良後的工具與技法,常見以蒸煮過的樹皮纖維做成紙漿,放入水槽調和後,用竹簾將纖維予以篩撈、重組成紙,烘乾後,適合用於毛筆書寫、繪畫。

1990年之後,歷經廠商外移東南亞、大陸出口紙低價競爭、國內學習書畫人口銳減等衝擊,紙廠家數急速下滑,埔里手工紙產業,宣告走入黃昏。

目前僅存的6家業者之中,廣興紙寮立足傳統,以高級紙質在書畫藝術界打響名氣,近年更開創文創紙的風潮,與美食、時尚結合,開發出可食用、可做布料的手工紙,成為造紙產業異數中的翹楚,替消失中的手工紙技藝,守住傳承與創新的最後一線生機。

1990年代初期,黃耀東希望兒子接班。這時,台灣的手工紙業已是日薄西山;三十多歲、沒有其他工作經驗的黃煥彰,只能硬著頭皮接下家業。

他注意到店內牆上掛著的書法作品,落款處寫著已逝書法家臺靜農的名字。「為什麼不直接賣給用紙的人?」就像絕處逢生,當下,他把憤恨與挫折,轉化成孤注一擲的決心。

黃煥彰坦承當時根本不知臺靜農是誰,也不認識任何書畫家,但「臺靜農」三個字,就像打在頭上的棒子,讓他頓悟,原來,廣興應該在乎的對象不是紙商,而是書畫藝術家。從那時起,黃煥彰開始蒐羅書畫名家的通訊錄,寄紙給他們免費試用。

寄送的紙張,陸續帶回書畫家們的建議,供廣興做為改進的參考。

除了傳統書畫紙,廣興近年將手工紙應用於文創的成績有目共睹,背後的靈魂人物是黃煥彰的妻子吳淑麗。

創意是吳淑麗的強項,她不停地思考,「手工紙還可以有什麼變化?」

好幾次,她在菜市場看到賣不完的菜被丟棄,覺得可惜,也興起嘗試用蔬菜造出食用紙的構想。

吳淑麗腦筋動得快,請黃煥彰幫她在廚房開闢一塊造紙區,除了必須特別要求衛生與清潔之外,流程幾乎與紙廠抄製書畫紙一模一樣。她使用的材料包括龍鬚菜、空心菜、地瓜葉、刺蔥、過貓、絲瓜、南瓜、辣椒等,終於在中華民國建國100年,發表100種可當點心或調味料食用的手工紙,命名為「菜倫紙」、「 paper菜」。

「造紙就跟編曲創作一樣,要有變奏跟曲風的變化,」吳淑麗開心地分享心得。

今年7月,她再發表可耐水的紙布,適合用來製作舞台道具服、租借服等。與食用紙不同的是,紙布的原料回歸樹皮纖維的使用,「手工造紙的『根』,我們還是留著,」她說。

文/朱立群 圖/莊坤儒

(摘錄轉載自102年10月《台灣光華雜誌》

全文請參考http://www.taiwan-panorama.com/)