可曾看過補丁的碗盤?這說明碗盤的紀念性,還有過去惜物愛物的觀念。圖/莊坤儒

可曾看過補丁的碗盤?這說明碗盤的紀念性,還有過去惜物愛物的觀念。圖/莊坤儒

每一只碗盤都記錄了常民生活的面貌,散發飲食文化的香氣。圖/莊坤儒

每一只碗盤都記錄了常民生活的面貌,散發飲食文化的香氣。圖/莊坤儒

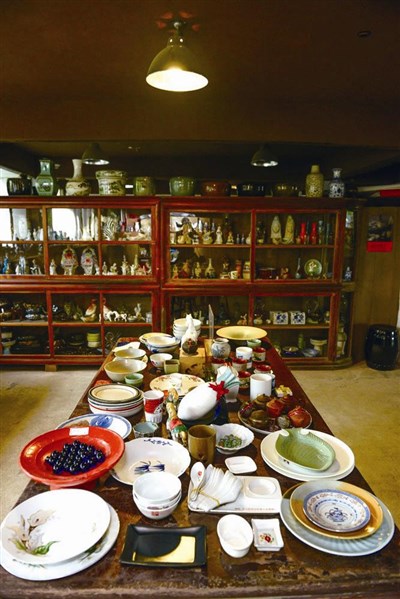

提供碗盤愛好者二手交換的交流區,是考驗眼力、尋寶的好地方。圖/莊坤儒

提供碗盤愛好者二手交換的交流區,是考驗眼力、尋寶的好地方。圖/莊坤儒

提要

不論貧富貴賤,一家人同桌共食,是最溫暖滿足的時刻。

碗盤與三餐飲食緊密相連,它記錄了常民生活的面貌,散發飲食文化的香氣。端起一只飯碗,碗盤上彩繪著紅澄澄魚蝦,訴說著人們對飲食溫飽的基本祈願。

宜蘭縣員山鄉的台灣碗盤博物館,建築物的前身是一個生產旅行箱的皮箱工廠,外觀樸實到讓人不經意就錯過。

When you enter the Bowl and Dish Museum, you are greeted by an enormous oval “fish platter,” 4.2 meters long and 3.0 meters high. This serving dish, 100 times larger than the ones you will find on ordinary dining tables, completely fills visitors’ line of sight, serving to block out the present day and tumbling them into a world of memory.

The Taiwan Bowl and Dish Museum occupies about 1600 square meters, and is divided into four areas: display, cultural/creative, cross-cultural, and hands-on. The display area, as the name suggests, is for the museum’s main collection. It starts with a brief history of the development of ceramic tableware over the years, both in Taiwan and around the world.

In the earliest days of human settlement, people in all corners of the world figured out that they could shape containers from handfuls of clay, thereby bringing ceramics into everyday life.

In the whole display area, the piece that Chien Yang-tung treasures most is a blue-and-white painted porcelain bowl from the Ming Dynasty. When he first acquired this piece, he knew only that it was quite old. It was only when excavation began at the Kiwulan archeological site in Yilan County that—amongst the many pottery shards of the indigenous Kavalan people—a similar porcelain bowl was discovered (albeit not a complete and intact specimen). This find was very exciting for Chien, for it suggests that even at that early time there was trade between Taiwan’s indigenous peoples and mainland China, and this porcelain bowl was probably there to witness it.

Then there are the countless items with auspicious meaning, like “fish platters” and “shrimp platters.” These were not necessarily designed to serve fish or shrimp, but merely had pictures of fish or shrimp painted on the bottom. “In a time when life was difficult, it was no easy thing to get real fish or shrimp in your dish,” says Chien. “The hopes and dreams of our ancestors were vividly expressed in the brushstrokes on their ceramic ware.”

Picking up a lard pot heavily marked by time, Chien explains that early ceramic tableware in Taiwan was very special in one particular way—almost all of it had “crackling” in the glaze. “Crackling” means that there is a large spider-web-like network of cracks in the glazed surface. This happened in Taiwan in the old days because early technology was inadequate, resulting in a thermal expansion mismatch between the clay and the transparent glaze. Once removed from the kiln and exposed to cool air, the surface would fracture into countless lines and cracks. “I suppose you would have to call these ‘rejects’ today, but they have a magic of their own. In particular, ceramic containers that were routinely placed in baskets for steaming food seem to have a hint of the aromas of the ingredients still ensconced in the surface fractures!” Chien, who can wax eloquently about every item he owns, sniffs at the used containers and asserts without reserve that he can detect the warm smell of lard.

Over the last two-plus years, the Taiwan Bowl and Dish Museum has held a number of events that have drawn very enthusiastic crowds. As Chien says, “We want the museum to be vital and alive, and the only way to do that is to link it with the living community around us, in the spirit of an eco-museum.” One of the first activities the museum organized after opening was to send a “tableware authentication team” to the nearby Yonghe Community. They invited the homemakers and elderly ladies in the community to search out old bowls, dishes, and other ceramic ware from their homes, and then everyone got together to share their “kitchen stories.” Chien assessed the womens’ ceramic ware for its age and authenticity, and everyone got a chance to marvel at the beauty(and monetary value)of these antiques. These women have rapidly become an important source of assistance for the museum, even preparing meals for museum events.

How about a “stamped” plate or dish? A “stamped” piece of tableware is one that has been marked with a symbol or family name for identification purposes. To the cognoscenti, this is also very revealing of rural life in days gone by. For big events like weddings, everyone in the neighborhood would pitch in not only by helping with the setting up and cooking, but also by lending their finest tableware. The only problem, when the party was over, was figuring out which dishes belonged to which household—hence the ID marks.

When you visit the Taiwan Bowl and Dish Museum in Yilan County, you will find a lot more than just thousands of examples of ceramic tableware. You will find yourself back in a slower, more leisurely time, a time when most people lived off the land and communities were close-knit. So come on along: How hard can a journey through time be when you can do it all in one place!

翻譯

走進碗盤博物館,迎面而來的入口意象,是一個長四點二公一百倍等比放大,讓參觀者視線完全融入盤中,跟著也跌進古老碗盤的記憶裡。

碗盤博物館占地約五百坪,館內共分為展示、文創、交流、體驗四區。展示區介紹碗盤發展的軌跡,從世界到台灣。

遠自初民時期,當世界各地的古老民族捧起一坯土,塑出可以盛裝器物的碗,碗盤就與每一天的生活緊密相連。又因為各地的風土、飲食習慣不同,產生各具特色的造型、色彩、圖紋。

在展示區裡,簡楊同最珍藏的寶貝是一只明朝的「青花排點碗」。當初購得這只碗,簡楊同只知道歷史久遠,但是直到宜蘭開挖淇武蘭遺址時,在眾多原住民噶瑪蘭人的陶瓷碎片中,挖出了相同的青花排點碗,但只有半個。這讓簡楊同特別興奮,這代表早在當時台灣的原住民與中國大陸已經有貿易交換行為了,而這青花排點碗就是見證。

看著碗牆上羅列的數千個飯碗,各具特色,幾乎沒有一個完全相同。每位工匠簡筆一揮,竹葉兩三片或小花一兩朵。更多則是祈願的魚盤跟蝦盤;「在生活艱困的年代,碗盤裡要有魚有蝦實在不容易。我們的祖先對生活的祈願,都在這寫意的筆畫裡了,」簡楊同表示。

再拿起一個浸潤了歲月痕跡的豬油罐,簡楊同接著表示,台灣早期碗盤,還有一個很大的特色:幾乎都有「開片」。這是由於早期的技術不夠好,陶土與表層透明釉的膨脹係數不同,一旦出窯遇到冷空氣,就產生了裂紋。「應該說這些都是瑕疵品,但是卻別具美感,尤其是經常放入蒸籠的碗盤,裂紋裡,更是保留了食物淡淡的氣味!」愛碗成痴的簡楊同嗅著老碗盤,直說還有豬油的溫暖味道。

私人博物館不論財力,人力總是有限。然而碗盤博物開館2年多來,卻舉辦了許多膾炙人口的活動。「結合社區資源,以生態博物館的精神來經營,博物館才有活力,」簡楊同指出。一開始館長就主動出擊,在鄰近的永和社區舉辦「碗盤鑑定團」活動。邀請婆婆媽媽們,找出家裡的老碗盤,大家聚在社區活動中心裡,一起分享碗盤的「灶腳」故事。而館長則幫媽媽們鑑定碗盤的歷史年代,並跟大家一起欣賞這些老碗盤的美感與價值。而這群媽媽們,很快就成為碗盤博物館的最大後援,還是活動主廚,為博物館上菜。

看過「補」過的碗盤嗎?看過「打字」的碗盤嗎?懷念粗陶碗裝著滷肉飯的絕配嗎?有著補丁的碗盤,說明碗盤的紀念性,過去惜物愛物的觀念。而你家娶媳婦宴客,鄰里們不只人來幫忙,家裡好的碗盤也都拿出來鬥陣。唯恐散席後,誰家碗盤分不清,因此各家碗盤都有各自的記號或姓氏。這些「打字」的碗盤,說明了傳統農業社會人際關係的緊密。

走進碗盤博物館,這裡不只是展示舊碗盤,還保留舊時光的悠閒,記錄農村社會人情互助的美好,讓我們藉著成千上萬的舊碗盤,一起「穿越」那個美好的年代吧!

文/蔡文婷 圖/莊坤儒

摘錄轉載自103年10月《台灣光華雜誌》

全文請參考

http://www.taiwan panorama.com/